mld2 /dt2

+

/dt2

+

d

d /dt

+

Wsin

/dt

+

Wsin =

Acos(

=

Acos( Dt)

Dt)

where the left hand terms represent acceleration, damping and gravitation, and the right hand side is the forcing term. In dimensionless form the equation can be rewritten as:

d2 /dt2

+

(1/q)d

/dt2

+

(1/q)d /dt

+

sin

/dt

+

sin =

gcos(

=

gcos( Dt)

where q is the damping factor, g is the forcing amplitude and

Dt)

where q is the damping factor, g is the forcing amplitude and  D

is the angular forcing frequency.

One may rewrite this differential equation as a set of first order coupled equations:

D

is the angular forcing frequency.

One may rewrite this differential equation as a set of first order coupled equations:

d /dt

=

-(1/q)

/dt

=

-(1/q) -

sin

-

sin +

gcos

+

gcos

d /dt

=

/dt

=

d /dt

=

/dt

=

D

D

is the angular frequency,

is the angular frequency,

is the angular position, and

is the angular position, and

is the phase of the forcing term.

(

is the phase of the forcing term.

( ,

, ,

, )

are the three dynamic variables necessary for chaos and the sin

)

are the three dynamic variables necessary for chaos and the sin and cos

and cos terms provide the nonlinearity.

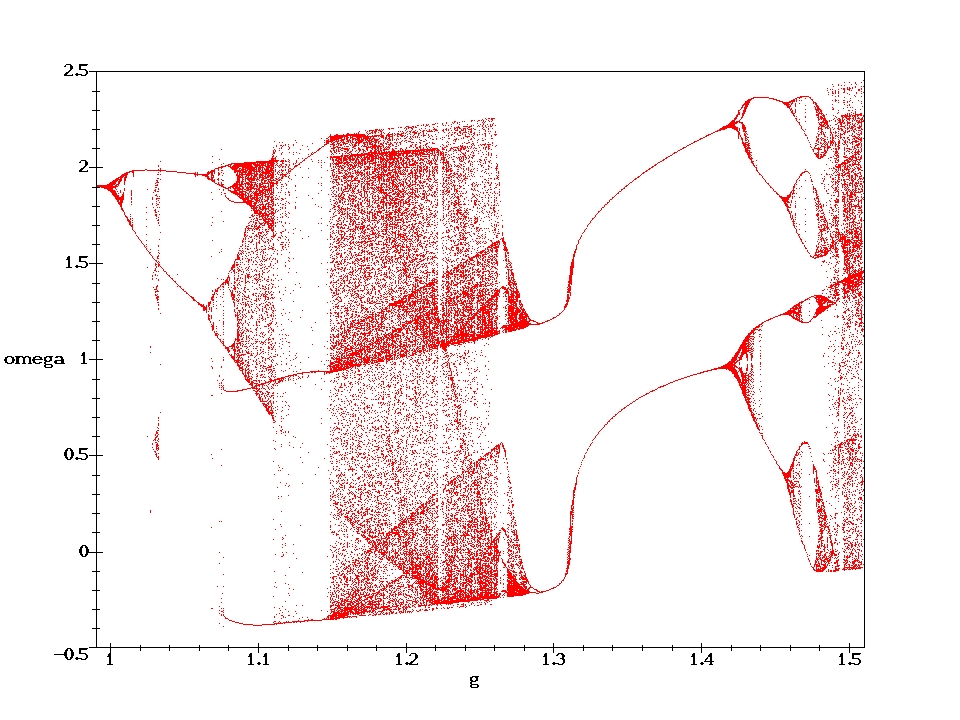

The pendulum displays a variety of ordered and chaotic

behaviour depending on the values of the parameters g,

terms provide the nonlinearity.

The pendulum displays a variety of ordered and chaotic

behaviour depending on the values of the parameters g, D

and q.

D

and q.

For small oscillations the undamped pendulum has a natural angular frequency of unity in the units employed here. Chaotic behaviour arises partly from the interaction between the driving frequency and the natural frequency so we can expect to find interesting behaviour for driving frequencies close to 1.

,

, ,

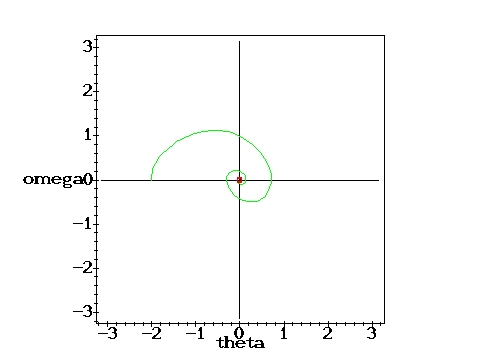

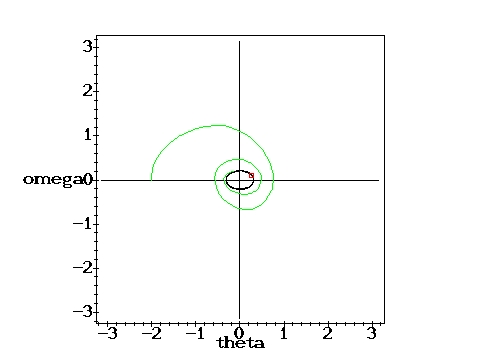

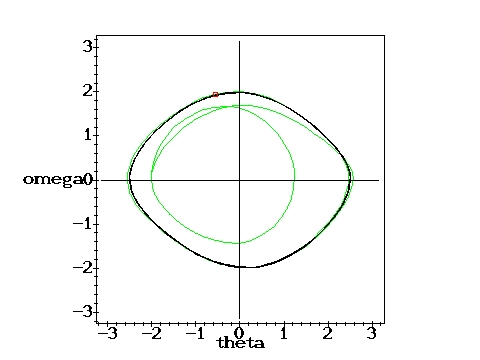

, as the coordinate axes. In the following phase portraits the phase trajectory is projected onto the

(

as the coordinate axes. In the following phase portraits the phase trajectory is projected onto the

( ,

, ) plane. In this plane periodic motion appears as

closed loops.

) plane. In this plane periodic motion appears as

closed loops.

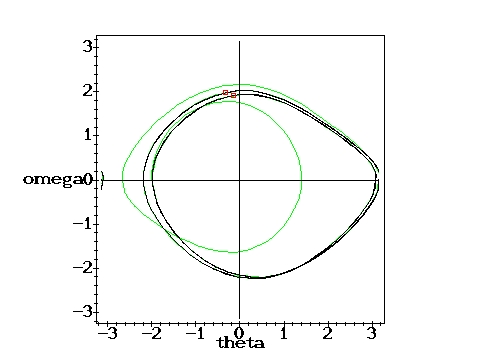

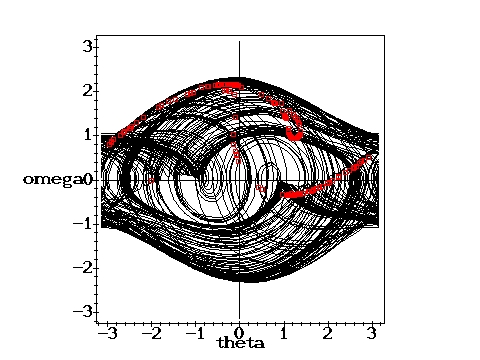

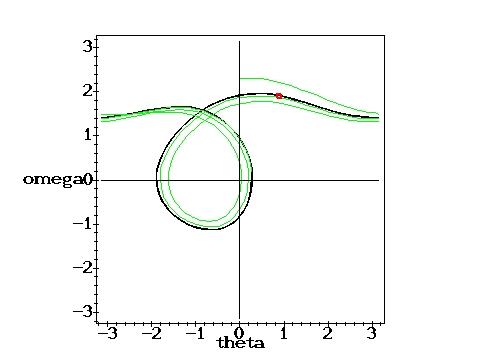

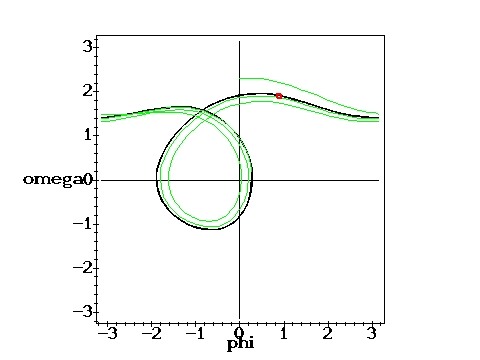

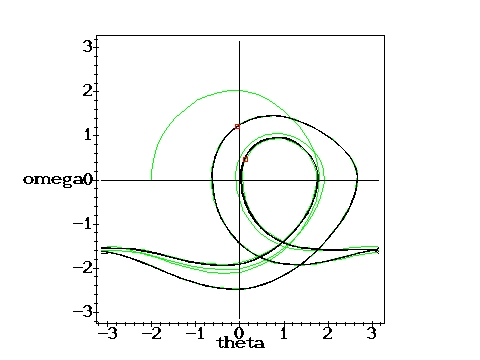

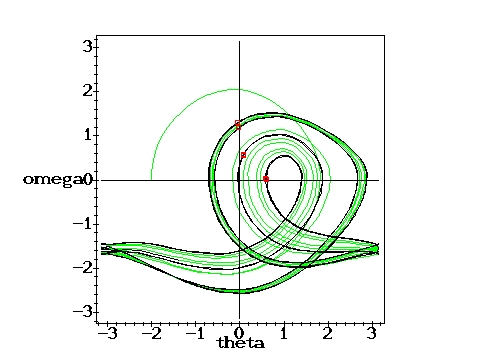

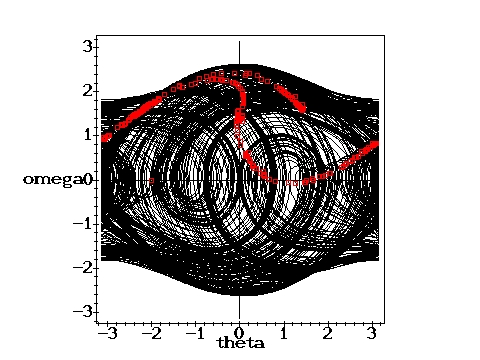

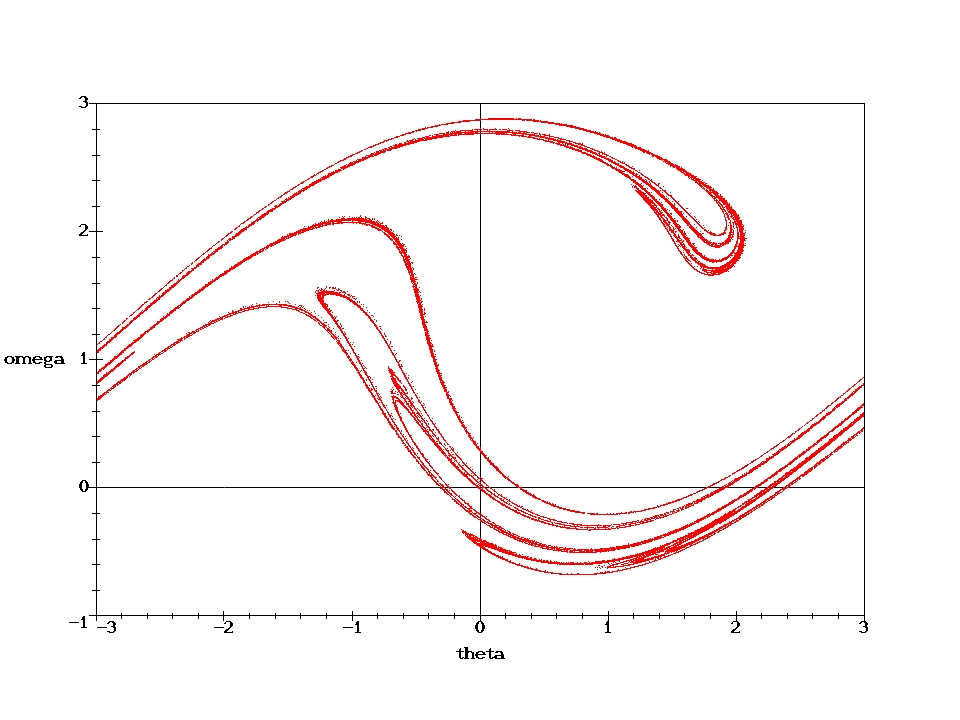

The green part of the trajectories indicates the initial oscillation before the motion becomes periodic. In the chaotic cases, the whole trajectory is plotted in black. The red points represent the Poincare section, which indicates the state of the pendulum after each period of the driving force. It therefore corresponds to a stroboscopic view at the pendulum in the phase plane. For the chaotic cases only a limited number of phase and Poincare points have been calculated. With the time approaching infinity, the corresponding phase plots would become uniformly black within certain regions and the Poincare sections would loose their discreteness.

|

|

Without drivin force: Damped oscillator. g=0, q=2,

D=0.6667 D=0.6667 |

Low driving force: Periodic motion.g=0.2, q=2,

D=0.6667 D=0.6667 |

|

|

Medium driving force: Single Poincare point.g=0.9, q=2,

D=0.6667 D=0.6667 |

Attractor with bifurcation: Two Poincare points.g=1.07, q=2,

D=0.6667 D=0.6667 |

|

|

Chaotic state: g=1.15, q=2,

D=0.6667 D=0.6667 |

Again periodic, single Poincare point: g=1.35, q=2,

D=0.6667 D=0.6667 |

|

|

Same force, different initial cond.: g=1.35, q=2,

D=0.6667 D=0.6667 |

Again a bifurcation: g=1.45, q=2,

D=0.6667 D=0.6667 |

|

|

Another bifurcation, four Poincare points: g=1.47, q=2,

D=0.6667 D=0.6667 |

Again chaotic: g=1.5, q=2,

D=0.6667 D=0.6667 |

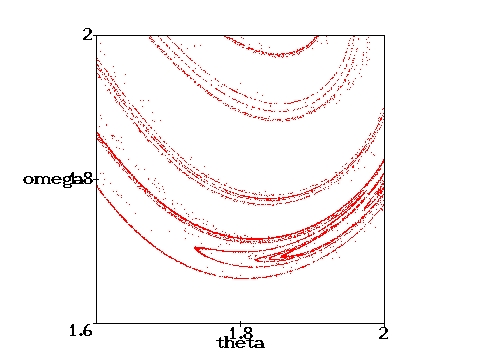

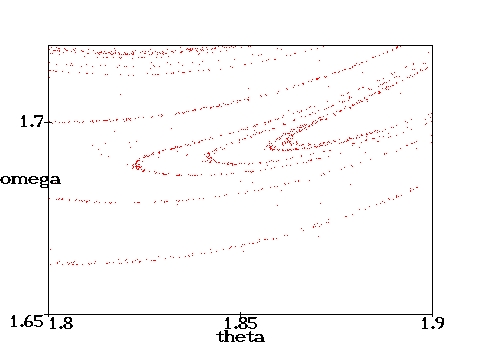

D=0.6667 (i.e., with a weaker damping than above) are shown. 100000 cycles have been computed. They nicely illustrate the self similarity of the Poincare section.

D=0.6667 (i.e., with a weaker damping than above) are shown. 100000 cycles have been computed. They nicely illustrate the self similarity of the Poincare section.

|

|